In summary:

- Human-centred design is shifting toward care-driven, trauma-informed approaches in public services.

- Ethical AI must be transparent, participatory, and designed to support—not replace—humans.

- Designers are becoming stewards, scaling impact through inclusive, pattern-based systems.

Fresh from three inspiring days at SDinGov in Edinburgh, our Experience Design Director Nicola Pritchard has been consolidating some of the key themes that stood out for her.

Designing for care

Rachael Dietkus, Founder, Social Workers Who Design

Rachael Dietkus, Founder, Social Workers Who Design

This was a recurring theme that resonated strongly across all three days; it signals a shift, beyond serving people (users, communities etc) to showing care in the way we design and operate our services.

Keynote speaker James Plunkett explored care through the lens of unshackling society and institutions from ‘bureaucratic machinery’ and called on designers to embrace and to visit the "human alternative." These alternatives demonstrate non-mechanistic, human-centred approaches to the systems and models we rely upon, from community development initiatives like Nudge Community Builders in Plymouth or Coin street builders in London and countless other examples, to alternative economic models and institutions as envisioned by the likes of Kate Raworth and The Oxford Centre for Human Flourishing. Organisations like Stir to Action help build that exposure by taking people on site visits to see initiatives in action, helping us imagine different pathways to solving today's problems.

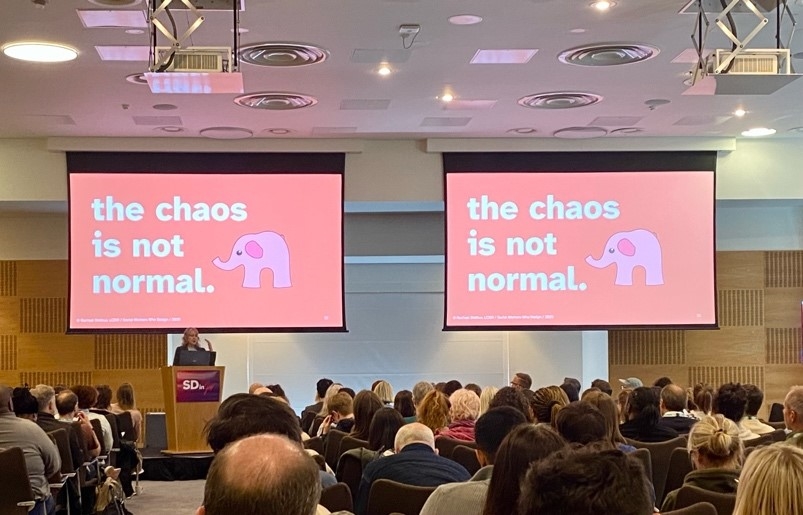

Social worker Rachael Dietkus described designing for care in her stirring presentation about civic trauma – the reality of living in a world where we're forced to accept and cope with profound distortion. She described the whiplash of switching between witnessing global suffering and engaging with trivial distractions like a quiz to find out ‘what kind of pop tart are you?’, all while knowing most systems are failing us. For Dietkus, designing for care means refusing “hypernormalisation”, advocating for broader adoption of trauma-informed service design that also recognises civic trauma, and developing a global code of care that can help shape and elevate the importance of care in how we design services and systems.

Intentional AI

Steph Wright from the Scottish AI Alliance reframed how we think about AI in public services. Rather than accepting AI through the lens of inevitability – "it's happening anyway, so we'd better adapt" – she advocates for intentionality. AI is just technology; its value comes entirely from the people behind it who set direction and generate meaning.

Wright reclaimed the label "luddite" from its mischaracterisation as anti-technology, emphasising that 19th Century Luddites weren't anti-tech – they were pro-people, advocating for technology that serves human needs rather than replacing human agency.

She gave the UK’s Participatory AI Harm Auditing Project and the Canadian government’s automated risk scoring as examples of this philosophy in action. In Canada’s case, (after concerted pressure from civil society) the government course corrected its approach to risk management through their Algorithmic Impact Assessment framework – ensuring that automated decisions are made in a way that is fair, transparent and accountable, through;

- Procedural fairness: departments must provide recourse options to challenge automated decisions and offer individuals a clear explanation of how the system arrived at a particular outcome.

- Human oversight: sets specific requirements for human involvement, with the level of oversight increasing for higher-risk decisions.

- Regular monitoring: systems must be monitored on a scheduled basis to safeguard against unintended consequences and unfair outcomes

These steps might seem obvious (and could definitely go further), but we're some way away from defining some global standards that are used wherever automated decisions are being applied. And when they’re not, Wright demonstrated the disastrous consequences, as seen in recent high-profile cases.

Wright also made the passionate case for empowering people to have a say in the design of AI through free and accessible training as well as advocating to design for failure, and to build awareness of the systemic exclusion that arises when power resides solely with the privileged few who are shaping AI technology across our public and private spheres.

Scaling through patterns

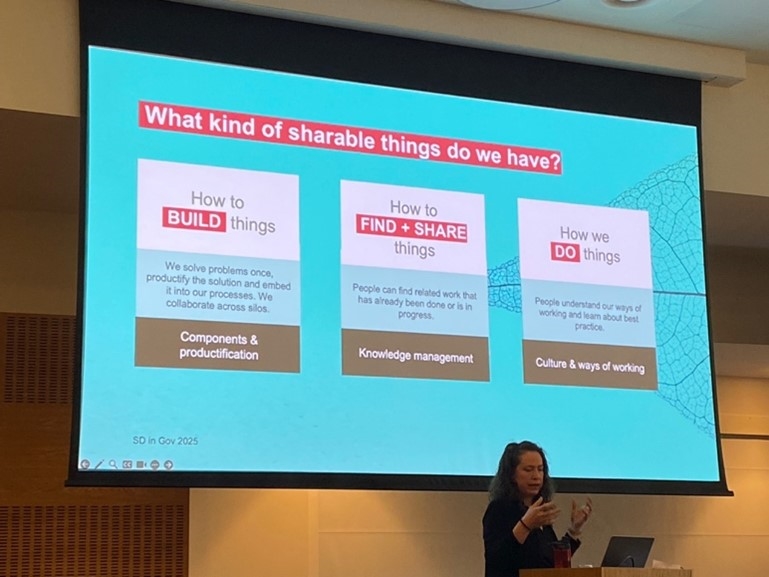

The conference lineup also addressed the more practical financial and resource challenges we face in the sector, through a few talks focused on pattern-based approaches. TPX Impact's workshop explored how we can develop service patterns for common interactions – applying, checking, accessing – using Sarah Drummond's Full Stack Service Design framework.

In the workshop, teams explored how "patternisation" extends beyond user flows and User Interface(UI) elements to include the multiple layers shaping the full stack underpinning our services; the organisational culture, the alignment with policy intent, the technical and procedural infrastructure supporting our services, and the organisation’s governance structures that power them. This more systemic approach to patterns and reusability was also echoed in the Ministry of Justice team’s talk on ‘Sharing and Reuse by Design’ (pictured below) and reinforced how pattern-based thinking can help both standardise and multiply our impact across government services whilst reducing duplication.

Nikola Goger, Ministry of Justice

Nikola Goger, Ministry of Justice

From craft to stewardship

Andy Marsden, Nesta

Andy Marsden, Nesta

Perhaps the most profound shift the sector is experiencing, has been the evolution of design away from more traditional design craft towards our role as design stewards.

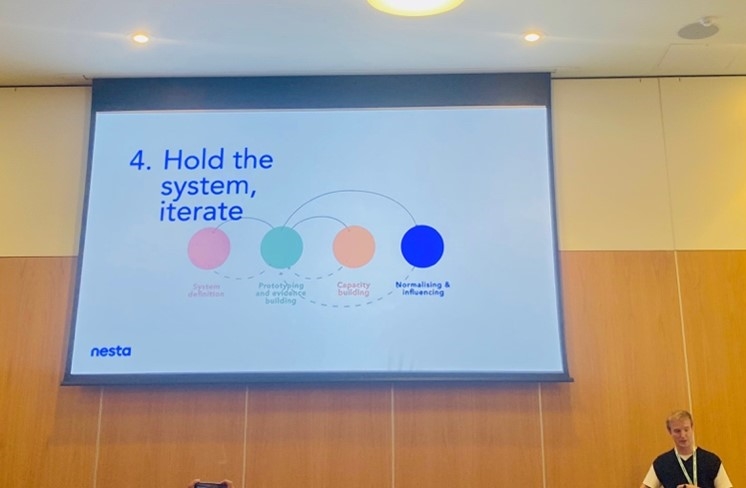

Whilst Lucy Kimbell noted in her talk that design craft is where we’re most vulnerable to non-human intervention, if James Plunkett is right that "design is the discipline of the moment," then our role is morphing into something new. Andy Marsden from Nesta described this as "holding the system" – maintaining space for others whilst shepherding them toward co-created aims with humility and openness. This might be a less tangible and measurable domain but is likely the secret glue that enables most high performing human centred programmes to succeed.

And of course it’s not just the design craft that’s evolving, traditional service design frameworks are too; from service blueprints to policy blueprints, from UI patterns to service and ‘full stack’ patterns, and from ‘service design’ to ‘public design’, where the boundaries of design influence begin to practically disappear.

Checking ourselves

Joanna Finlay, Sopra Steria

Joanna Finlay, Sopra Steria

SDinGov is designed with and for design advocates, so it’s important for designers to keep themselves in check, and, crucially, to bring non-design voices into the room. Sopra Steria teammates Jonti Dallal Small and Joanna Finlay explored this very theme in their session ‘Rewiring the Juggernaut’ making the case for, and sharing practical tools, around how to embed human centredness into the knotty mechanics of large digital transformation programmes, centring and working with people within the wider programme who are focused on areas such as governance, risk, and performance, rather than butting heads with them (at best) or ignoring their existence (at worst). They’ve created a super helpful summary worksheet that you can access here.

But this isn’t about making ‘design’ the governing discipline. Focusing on any professional wrapper ultimately detracts from the real goal: creating products, services, institutions, policies, practices, and systems that work better for people. If the beauty lies in achieving what James Plunkett described as an "integrated and balanced government settlement" – we know that the richer the pool of disciplines and worldviews the more successful the outcomes, and it is ultimately what will enable all disciplines to embed care for humanity and hopeful intentionality into what we build and how we build it.

Most importantly, no matter the hat we wear professionally, we all have unique tools for expressing civic care (to use Dietkus’ framing). The question isn't, and never should be, whether design matters, but how we can all contribute to more caring, human-centred approaches to public service. And speaking of care....here’s a picture of a very caring bunch from the Sopra Steria family. Nicola for one will miss them as she goes off on maternity leave next week!

See you all at SDinGov, 2026!

Left to right; Nicola Pritchard, Sophia Klinck, Margaret Moore, Henry Bacon, Jen Senior, Joanna Finlay (and Jonti Dallal Small, who was with us at the conference but managed to escape the photoshoot!)

Left to right; Nicola Pritchard, Sophia Klinck, Margaret Moore, Henry Bacon, Jen Senior, Joanna Finlay (and Jonti Dallal Small, who was with us at the conference but managed to escape the photoshoot!)